Anuj Amin | Divine Prisons and Sacred Bindings: Late Ancient Aramaic Incantation Bowls

Anuj Amin | Divine Prisons and Sacred Bindings: Late Ancient Aramaic Incantation Bowls

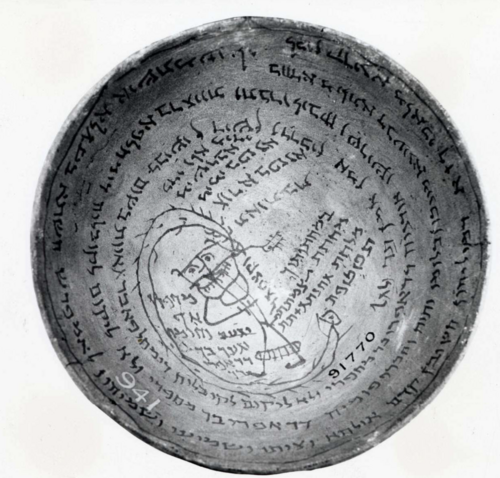

Ancient practitioners of Judaism, Zoroastrianism, and Christianity had substantial differences, but they agreed on one crucial issue—they lived in a world infested with demons. Some possessed human bodies, causing physical and mental harm. Others, incarnations of Adam’s first wife Lilith, blackened the wombs of women and ripped life from unborn children. And certain demons even lived in the courts, swaying judicial opinions and weaking the confidence of lawyers. By the fourth century, demons had fundamentally altered the lives of humans throughout the Middle East. Possession was rampant, and humans were vulnerable. In response, Jewish, Christian, and Zoroastrian priests forged a powerful a solution to this problem—enchanted bowls.

First brought to scholarly attention in 1913, Aramaic incantation bowls have since become the subject of translations, private collections, and museum holdings. Originating between the fourth and seventh centuries in what is now Iraq and Iran, over 2,000 of these bowls are currently held by museums and private collectors worldwide. The inscriptions are in multiple dialects of Aramaic, including Jewish Babylonian Aramaic, Syriac, and Mandaic, and they often blur the lines between different religious cosmologies.

Despite the rich insights these bowls provide, several key questions remain unresolved. What accounts for their sudden emergence during the Sasanian period, and what factors contributed to the decline in their use by the seventh and eighth centuries? Also, what roles did they play in ritual practices? My project, "Divine Prisons and Sacred Bindings: Late Ancient Aramaic Incantation Bowls," seeks to address these questions through a multidisciplinary approach that incorporates perspectives from philology, legal history, digital humanities, medical anthropology, and art history.

The Europe Center's summer grant enabled me to advance this research by visiting the British Museum, where I had access to a unique collection of bowls that deviate from conventional designs. For example, bowls held by the British Museum seem to demonstrate an inversion of function—individuals could summon demons using these bowls. The museum also has several bowls that demonstrate a rich interplay between writing and imagery that will be explored further during the academic year. Ultimately, the experiences afforded to me by the Europe Center allowed me to collect invaluable data, and many of the bowls from this collection will serve as case studies in my dissertation.