Benjamin Doughty (Genetics) | Effects of chromatin remodelers on genome structure at single-molecule resolution (EMBL Heidelberg)

Benjamin Doughty (Genetics) | Effects of chromatin remodelers on genome structure at single-molecule resolution (EMBL Heidelberg)

I was fortunate to spend the summer of 2025 working with Dr. Arnaud Krebs at the European Molecular Biology Lab (EMBL) in Heidelberg. During his postdoc, Dr. Krebs, who now runs a research lab in the Genome Biology division at EMBL, invented a technique called single-molecule footprinting (SMF), which provides unprecedented resolution into the basic molecular interactions that control life. I have made extensive use of SMF throughout my PhD, so I jumped at the chance to conduct research with and learn from Dr. Krebs.

In order to carry out their unique functions, different cells (e.g. neurons, pancreatic β-cells, etc.) must turn on different genes and specific times that are unique to their role, and they do this using a combination of DNA binding proteins. Prior methods for studying these proteins involved grinding up millions of cells, averaging signals and obscuring the underlying heterogeneity inherent in these processes. However, SMF (essentially a molecular can of spraypaint) allows you to measure these binding events on individual molecules of DNA, which facilitates analysis at the fundamental unit of regulation.

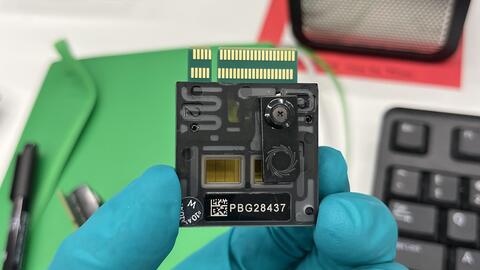

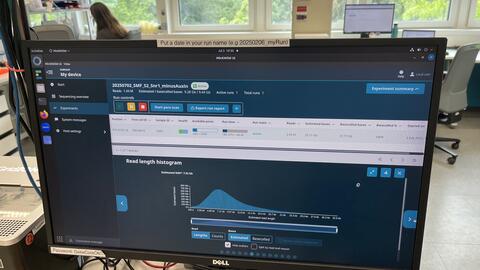

During my internship, I used SMF to profile the effects of chromatin remodeler perturbations on genome structure. In cells, DNA is packaged by proteins called histones into a higher-order structure called chromatin. Histones allow for DNA to be compacted enough to fit inside the tiny cell nucleus, but DNA must be accessible in order to be read, implicating the exact positions of these histones in gene regulation. Chromatin remodelers are proteins that move these histones around on DNA and are essential for eukaryotic life. I used SMF to measure what happens to genome organization (i.e. where are the histones) when different remodeler proteins are knocked out genetically in Drosophila (fruit flies). First, I had to write a probabilistic model to analyze the resulting data to identify the positions of these histones in my data (software Ibelieve will be broadly useful to my host lab and the wider community). Then, I used this code to identify both widespread loss of chromatin accessibility as well as subtle shifts in histone positioning and regularity after the loss of these remodelers. I left behind more data that will be sequenced over the next few months, and we plan to write up these results into a brief publication.

Outside of the lab, I had the chance to present some of my findings at a conference organized by my host, which was fortuitous timing! I also visited the lab of a personal scientific hero in Basel, Switzerland, accidentally interviewing for a postdoctoral position in the process. Living and working in Heidelberg was amazing: my commute involved biking up a mountain, through a forest and past fields full of cows and wildflowers, and I often spent long summer evenings riding through the vineyards north of the city or drinking local beer in the meadows on the banks of the Neckar.

Life at EMBL was also a change from Stanford – the atmosphere was more relaxed and collegial, and I will miss gathering with my labmates every day to eat lunch together at the (subsidized and delicious) Mensa. I was also fortunate to travel on the weekends, taking the Deutsche Bahn to visit friends in Freiburg (Ariel, a former GRIP fellow!), Berlin, Ulm, Zurich,and Paris. I hope to be able to return to Heidelberg, EMBL, and the Krebs lab next summer to finish up the work I started.