Colin Madaus (Mechanical Engineering) | Direct Injection Hydrogen Emissions Modeling and Mitigation (Technical University of Munich)

Colin Madaus (Mechanical Engineering) | Direct Injection Hydrogen Emissions Modeling and Mitigation (Technical University of Munich)

This summer I had the privilege of conducting research at the Technical University of Munich (TUM) in the Institute for Sustainable Mobile Powertrains under the guidance of Professor Malte Jaensch. There, I worked on a project funded by Rolls-Royce Power Systems MTU Friedrichshafen GmbH (hereafter “MTU”), investigating the feasibility of direct injection hydrogen combustion in medium and slow speed diesel engines. The ultimate goal of this research is to demonstrate whether engines can achieve diesel-equivalent power output using pure hydrogen, while drastically reducing the global emissions footprint of shipping and stationary power.

Hydrogen continues to occupy a central role in global research and innovation due to its potential as a carbon free energy source. Its high specific energy per unit mass and compatibility with renewable energy systems make it attractive for decarbonizing transportation and power production [Source]. Importantly, hydrogen enables sector coupling: renewable electricity can be stored as hydrogen and later reconverted for mobility or grid balancing.

However, hydrogen is not without challenges. Its use in combustion systems reveals unique anomalies that remain the subject of ongoing research:

- Hydrogen has an exceptionally wide flammability range and high flame speed, leading to challenges with knock, pre-ignition, and backfiring.

- Most hydrogen production today is still fossil based, primarily via steam methane reforming (SMR), which undermines its decarbonization potential.

- Hydrogen combustion produces nitrogen oxides (NOx), a major pollutant with both climate and air-quality impacts. In hydrogen engines, lube oil additives and crevice gases can increase NOx formation.

- Its low volumetric energy density creates major storage and transport challenges, requiring either high-pressure tanks, cryogenic storage, or chemical carriers.

- Global infrastructure remains underdeveloped, and uncertainty in standards, policy, and investment slows widespread adoption.

The maritime industry is under unique pressure to decarbonize. The World Economic Forum estimates that shipping produces over one billion tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions annually, while carrying more than 80% of global goods [Source]. Most ships today burn heavy fuel oil (HFO) or marine diesel oil (MDO), which are cheap but extremely polluting. HFO can contain up to 2,000X more sulfur than road diesel, producing sulfur oxides, particulate matter, and carbon dioxide. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) has introduced regulations such as the IMO 2020 sulfur cap and is moving toward net-zero greenhouse gas targets by 2050 [Source: MARPOL Annex VI].

One of the greatest obstacles to implementing alternative fuels in shipping is infrastructure lock-in. Retrofitting the global fleet with entirely new propulsion systems and fuel storage would be massively expensive. Therefore, solutions that align with existing engine platforms, like retrofit direct injection hydrogen are attractive because they leverage existing assets while decarbonizing shipping.

Combustion research begins at the molecular scale. A simple reaction A + B → C can be described by a rate equation, but in real fuels dozens to hundreds of reactions occur simultaneously. Solving this system requires numerical approaches.

Chemical kinetics solvers such as Cantera, Chemkin, and Converge, allow researchers to track intermediate reactions using detailed mechanisms. These mechanisms are validated using shock tube experiments, where laser absorption spectroscopy measures transient species under controlled high-temperature, high-pressure conditions. During the past year at Stanford, I used Cantera to model the pyrolysis of methane into hydrogen gas.

Once validated, mechanisms can be scaled up to model engine combustion, though uncertainty grows significantly because of turbulence, mixing, and wall effects.

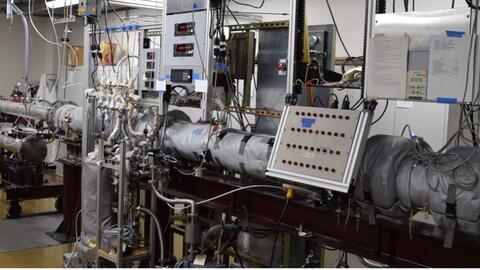

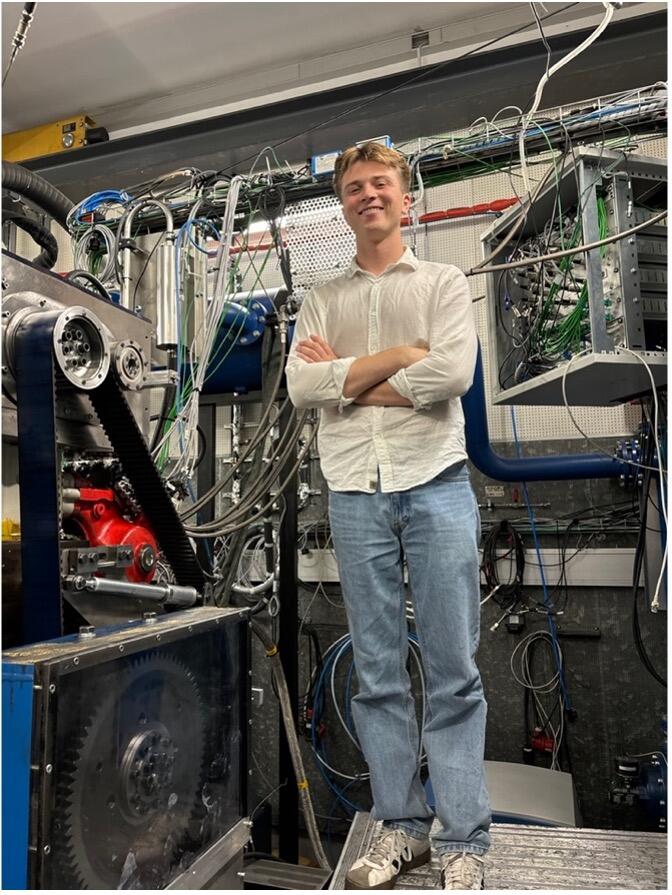

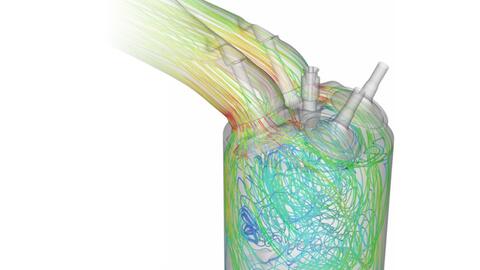

At TUM, the research team employed a single-cylinder, large-bore diesel engine fitted with a prototype direct hydrogen injection nozzle developed by MTU. Available measurements included: In-cylinder pressure sensors, Intake temperature, pressure, and air-fuel ratio (AFR) and exhaust gas sensors (for NOx, H₂ etc). A prior study at TUM based on port-fuel injection hydrogen had produced a preliminary empirical model of NOx formation. My research compared this model against the Zeldovich thermal NO mechanism and its extensions.

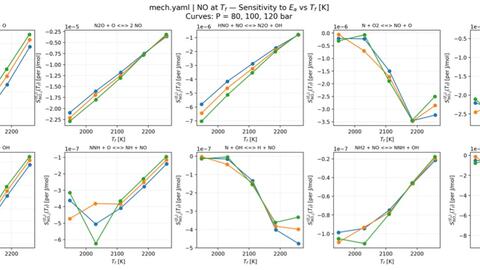

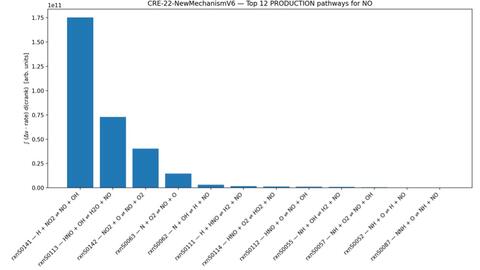

Using 0D zero-dimensional reactor simulations in Cantera, I conducted a reaction pathway sensitivity analysis across AFRs and initial conditions. This analysis identified which NOx formation pathways were most influential, highlighting “dials to change” in the mechanism to better align predictions with experimental outcomes.

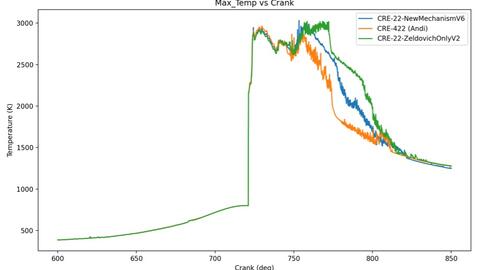

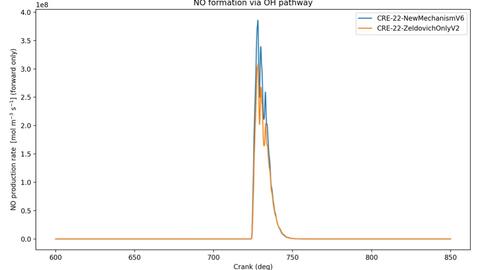

Next, I conducted three-dimensional modeling of the engine cylinder to evaluate how the institute’s existing NO modeling techniques compared with both traditional approaches and a previously validated port-fuel-injection (PFI) model from an earlier campaign. The comparison revealed mismatches: the prior model overpredicted thermal NO formation under lean conditions and underpredicted NO contributions in near-stoichiometric cases.

This analysis helped identify the dominant reaction pathways for NO formation, allowing the research team to focus on the most influential reactions when modeling NOx production in direct injection (DI) hydrogen combustion.

The CRE-422 mechanism, developed in-house, represents a simplified PFI-based model currently being adapted for DI conditions. The CRE-22 mechanism is an extended Zeldovich formulation that includes OH-mediated pathways and serves as the proposed model for DI NOx formation. Lastly, the CRE Zeldovich-only mechanism is a commonly used simplified mechanism widely used for general thermodynamic and combustion simulations. The Zeldovich only mechanism significantly underestimates NO formation under hydrogen conditions. These findings allow the research team to compare measured exhaust NO concentrations with the three modeled mechanisms, identify which reaction pathways most influence emissions, and reduce the time and computational cost required to refine a validated reaction mechanism for DI hydrogen combustion.

Although the retrofit engine build was still underway during my stay, the team is scheduled to begin experimental campaigns in late September 2025. My modeling results will provide the baseline for interpreting those experiments and refining the predictive NOx models. A joint publication is planned once experimental validation is complete.

My experience bridged the gap between fundamental combustion kinetics at Stanford and applied engine research at TUM. As I transition to the U.S. Coast Guard’s Marine Safety Center, I will carry with me a deeper understanding of the scientific, engineering, and regulatory layers of propulsion innovation. This perspective will be invaluable as the Center evaluates new vessel designs, approves advanced propulsion systems, and contributes to international standards through the IMO.

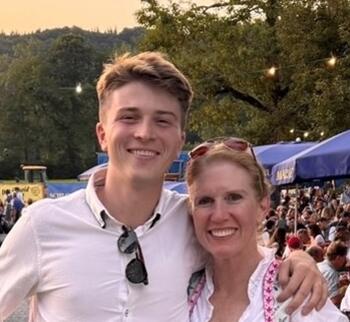

I would like to thank Capt. Doherty, LCDR Yin, and LCDR Sysko for enabling this opportunity, along with Shannon, Alyssa, and everyone at the Freeman Spogli Institute for supporting my participation in GRIP. Special thanks to Prof. Ron Hanson, Dr. Jesse Streicher, and Gibson Clark of the Hanson Group at Stanford for their mentorship in reaction kinetics and shock tube methods, which directly prepared me for my work at TUM. Of course, deepest gratitude to Prof. Jaensch, Prof. Prager, Felina, Moritz and Andi for all their guidance this summer at TUM.