Laura Menendez Gorina | Inhabited Ruins: Narratives of Homes from Modern Barcelona and Havana

Laura Menendez Gorina | Inhabited Ruins: Narratives of Homes from Modern Barcelona and Havana

“Domesticity, privacy, comfort, the concept of the home and of the family: these are, literally, principal achievements of the Bourgeois Age.”

John Lukacs, “The Bourgeois Interior”

“The growing sense of domestic intimacy was a human invention as much as any technical device. Indeed, it may have been more important, for it affected not only our physical surroundings, but our consciousness as well.”

Witold Rybczynski, Home: A Short History of an Idea

When and how did our concept of the modern home emerge and what did it entail? How did it affect the ways in which we represent reality and conceive of space? How did literary and cultural artifacts manifest that change? The concept of home is as much a cultural construction as cultural ideas such as childhood and family are, and it cannot be understood without reference to its specific history. Emerging mainly as a bourgeois concept as notions of privacy and comfort built up, its development has had implications in our thinking of modernity and of the modern household. Tracing the evolution of its configuration and, in so doing, reexamining a bourgeois tradition that profoundly shaped it, implicitly brings us to a criticism of modernity and of uneven processes of so-called progress. My investigation brings us to the cities of Barcelona and Havana at the end of the nineteenth century to scrutinize how the modern configuration of dwelling that arose in the Catalonia of the time was deeply imbedded to its colonial counterpart – that of the island of Cuba –, which not only provided the necessary funds to carry out the modernization of the city and its housing scene, but also influenced the aesthetics and imaginaries of what ought a house represent.

The idea of privacy that led to our concept of modern housing had already been developing for long before the 18th century as the workspace gradually became physically – and mentally – separated from living space (Rybczynski 1986). As the house was becoming exclusively a residence, a growing sense of intimacy arose as well, and “home” became progressively identified with family life. This turned especially notorious as the bourgeoisie fully established as a social class, which in nineteenth-century Barcelona came into being by means of a considerable industrialization process ahead of the rest of Spain. Industrialization and technological advances improved general living conditions at large. This prosperity brought about a huge demographic increase which prompted a great proliferation of urban transformations, similar to those carried out in other European cities such as Haussmann’s in Paris or Hobrecht’s in Berlin. As the streets mutated, new housing needed to be accommodated. With great avenues such as Barcelona’s Expansion District of the ‘Eixample,’ the house gradually transformed. But their physical reconfiguration not only altered urban landscape and interior taste and décor; it also reshaped behaviors and attitudes around the home and the multiple meanings attached to them.

In La febre d’or (The Golden Rush, 1890-92) by Catalan novelist Narcís Oller one can trace how the new ‘modern,’ bourgeois family found in the space of the house a means to showcase its recent status ascent. As the main character, and father of the leading family, quickly becomes rich by speculating in the stock-market during the ‘gold rush’ of the 1880s, the house transforms and becomes a key component in securing the family’s wealth. Especially revealing is how the narrative unfolds: emerging from humble origins, the head of the family travels to Cuba to learn the vicissitudes of entrepreneurship. Although the experience turns into a failed enriching attempt, his stay in Havana provides the man with the skills necessary to understand how business operates. It is through this expertise that he is able to perform his rapid ascent upon his return to Barcelona. But just as the dream of easy enrichment in Cuba resulted in fraud, his later success in Catalonia would soon encounter its ruin. Not only will his enterprises end up in bankruptcy; the family will also lose their sumptuous newly acquired house to go back to the humble flat where they started. My research scrutinizes the nuanced intricacies of how the home is represented in works of art as such, as huge urban transformations were altogether reshaping what the meaning of home entailed.

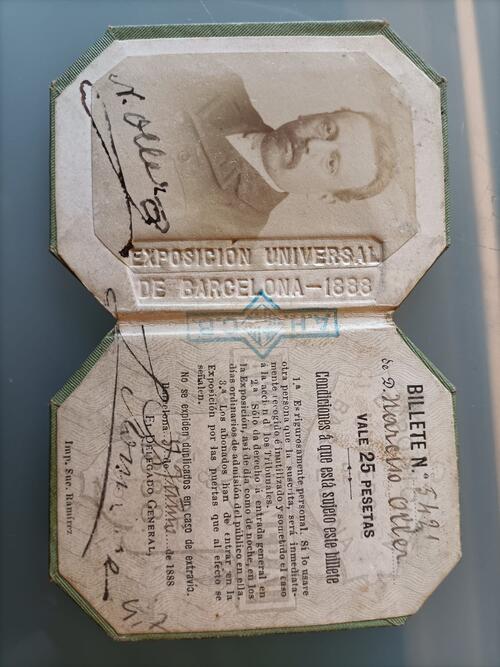

Thanks to the generous support of The Europe Center, during the past Summer I was able to spend a month and a half conducting archival research in Barcelona’s Arxiu Nacional de Catalunya (ANC) and Arxiu Històric de la Ciutat de Barcelona (AHCB). Researching into these two key archives allowed me to deepen into how the modern house of the city unfolded, as well as into the economic linkages with Cuba’s colony and the novelist’s influences in determining Barcelona’s configuration of a modern image. At the ANC, I was able to research through the minutes and memoirs of the Banco de Barcelona, the financial institution that sponsored many of the crucial modernization ventures of the city from the Universal Exhibition of 1888 to urbanism and real-state enterprises of the time. Significant results included the investments of the magnates ruling the bank company into Cuban trade, some of them through the slave trade, that allowed the members to reinvest their capital into philanthropic activities and housing construction in the metropolis, greatly advancing the modernista aesthetics that was to lead the city’s modern image.

At the AHCH I had the opportunity to consult maps, urban plans, housing sketches and layouts, among others, that confirmed the proliferation of modern housing in the city during that time. The archives also allowed me to glimpse into the life and thinking of the author through a specialized collection including his memoirs and photographs. His writings proved an important testimony to the industrialization and growth of Barcelona of the era, the magazines and literary circles’ influences that accompanied his ideas on progress, and his personal experiences in modern domestic life. At the collection, I could also consult correspondence with other intellectuals of the time and a generous album of photographs including evidence of his participation in key events such as the 1888 Exhibition or the Jocs Florals or of his personal residence and interior décor. Inspecting his memoirs and letters also afforded locating some of the settings portrayed in the novel and better understanding the meaning that the author attached to them.

My summer research stay in Barcelona aimed to scrutinize how urban planning during the fin de siècle and beginning of the twentieth century in the city, along with this key Catalan novel that captured the urban imaginary of the time, projected and configured a particular idea of the domestic space. I did so by arguing that Barcelona’s modern urbanism and its dwellings couldn’t have equally unfold without the exchange of capital and ideas with Cuba’s colonial counterpart. In this way, in this research project I contended that some of the central elements that gave rise to a modern image and consciousness to the city, such as the modernista aesthetics or the economic boom of nineteenth century’s stock-market or of the repatriation of capital from returned successful Catalan businessmen from Havana – which partly provided the means for the material construction of Barcelona’s modern built environment –, have cultural and economic roots in a complicated interrelation between Catalonia and Cuba as both centers and margins from Spanish imperial and national control. I thus show how modern housing emerged from an imaginary of modernity deeply affected by colonial relationality, captured and refigured by authors and artists in their works.

This relationality is nonetheless twofold. Homes in Barcelona were influenced by those in Havana in their arrangement of space, decoration, and habits, as many returned indianos, in order to demonstrate their success, indeed reproduced in their residences many of Cuba’s motifs. At the same time, the cross-cultural exchange prompted the propagation of a modernista aesthetics in Havana’s homes, aided with the presence of migrated Catalan architects in the island. Thus, the story seems in a way to come full circle. The circle is, however, still quite incomplete. Going back to Oller’s novel, it is curious to observe that, despite its totaling ambition to reproduce the reality of the time as a key national realist text at the level of those of De Queiros, Galdós, Tolstoi or Balzac, it greatly omits the emergence of the proletariat and the tensions of social class struggle. This rapid growth did not happen without its counterpart: despite sanitation efforts, next to sumptuous dwellings lied precarious homes, many of them from the blue-collar population that worked in the factories – such as of the textile industry – that allowed the American transatlantic trade. Theirs were indeed the homes with which the CIAM movement focused on developing modern households.

At the same time, in Havana, many of the modern buildings and mansions built by Catalan businessmen soon became appropriated by the proletariat and divided into multiple households, giving rise in many cases to so-called ciudadelas or solares in Cuba’s capital. Today many of these buildings lie in ruins, abandoned by time, lack of resources and neglect, as Barcelona’s construction ambition brings gentrification and marginalization to the level of home. Most of this housing continues to be inhabited. Depending on what perspective you look from, modernity turned houses into ruin. In this way, when engaging with the study of modern projects of home, one also needs to pay attention to those who were excluded from it, or in other words, suffered their consequence. This is precisely where my next chapter of the dissertation starts off.

I am grateful for the support of The Europe Center in being able to carry out the research necessary to conclude the first chapter of my dissertation and build solid basis from which continuing to construct more.

Works Cited

Rybczynski, Witold. Home: A Short History of an Idea. Viking Penguin Inc, 1986

Lukacs, John. “The Bourgeois Interior,” American Scholar, Vol. 39, No. 4 (Autumn 1970), pp. 620-621