Mary Kate Gale (Bioengineering) | Implementation and Verification of Gaze-Tracking for the da Vinci Surgical System (Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems)

Mary Kate Gale (Bioengineering) | Implementation and Verification of Gaze-Tracking for the da Vinci Surgical System (Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems)

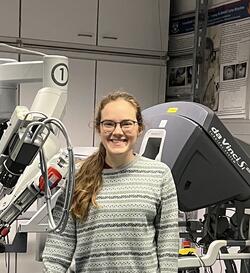

This summer, I worked with Dr. Katherine Kuchenbecker at the Haptic Intelligence Department of the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems in Stuttgart, Germany. This group has collaborated in the past with my home lab at Stanford, and I am not the first student to be sent between the labs! At Stanford, my PhD work involves designing optimal training methods for clinicians to learn how to use surgical robots. With this summer visit, I wanted to get experience with more hands-on robotic system design, so I worked to implement a gaze tracker on a da Vinci surgical robot.

In the context of robotic surgery, gaze tracking can be useful both as information about the user and as a mechanical input. Knowing where a surgeon is looking while they operate can be important for understanding their mental state by determining what they are paying attention to and whether they are distracted. Gaze location can also be used as a robotic input, as you can design systems where surgical tools can be manipulated by gaze location rather than traditional physical controls.

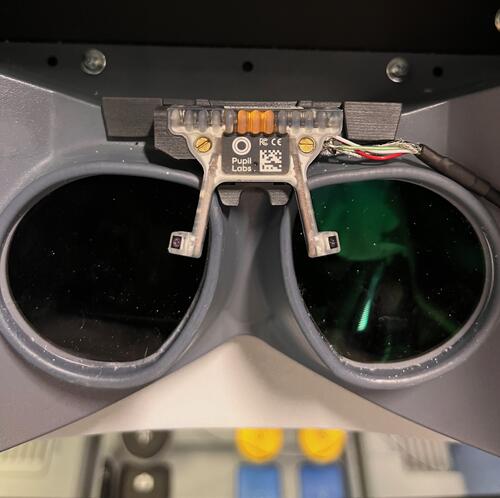

When I arrived at Max Planck, they already had a commercially available gaze tracking system, the Pupil Labs Neon. To keep a stable translation between the frame of the gaze tracker and the frame of the da Vinci, we statically mounted the module on the robot console. This posed a problem, however, because the gaze tracker was designed to be worn on and move with the head. This difference between the intended and actual use meant that when a user moved their head at the da Vinci console, the accuracy of the gaze tracker decreased. I worked to solve this by tracking the position of the eyes in 3D space and creating (and comparing) several different regression models to correct for head motion. I was able to significantly increase the system accuracy to the point where it was a viable stream of information.

Once I had this system set up and calibrated, I used it as an input to a robotic controller. I created some demos of the power of gaze control, including a haptic system where a user’s gaze location on screen controls the motion of the robotic arms they are holding – it almost felt like the robot was reading your mind!

Other researchers from my group are already planning for experiments using the system that I refined. One student is interested in tracking cognitive load on surgeons during a robotic operation, and they plan to use the gaze tracking system alongside skin conductivity to monitor surgeon attention and cognitive demand. Additionally, my immediate team plans to write the specifications of the gaze tracking system into a scientific publication that can be shared with other researchers who are interested in integrating gaze tracking into their surgical robotics work.

Beyond my work, I had a wonderful time both inside and outside of my lab. At the beginning of my internship, I was able to go to Schluchsee in Schwarzwald for a three-day Department retreat, which was a wonderful way to get to know my coworkers (and experience not-so-sunny German weather)! The researchers at Max Planck were a diverse group, with the majority of my coworkers being international. This was helpful as I became accustomed to my new life in Germany because many of my new friends had similar experiences adjusting. I will fondly remember working on jigsaw puzzles, hosting Teeklub, attending the Stuttgart Pride parade, and traveling to South Korea for a conference with my group at Max Planck.

My favorite part of where I lived was the amazing access to public transportation. I lived in a flat on a quiet, green street that was somehow both a ten-minute walk to a dense forest and a twenty-minute bus ride to my work – that would never happen in the US! I made great use of my monthly transit pass and spent every weekend visiting places in the greater Stuttgart area and a bit farther afield. I traveled to Geneva to visit a friend working at CERN, Hamburg to run a half marathon, and Strasbourg to see the EU Parliament – all by train.

My research stay at Max Planck was rewarding, both professionally and personally, and I will remember the time fondly. I am glad to have made so many connections and learned so much. I miss Max Planck already and am looking forward to when I can next return!