Dylan Britt: Connecting Galaxies and Dark Matter (University Observatory Munich)

Dylan Britt: Connecting Galaxies and Dark Matter (University Observatory Munich)

During my GRIP internship, I conducted research at the Universitäts-Sternwarte München (University Observatory Munich) in the group of Professor Daniel Grün, who is the Chair of Astrophysics, Cosmology, and Artificial Intelligence at the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität. I studied the statistical connection between the distributions of galaxies and dark matter in the universe, which is a focus of my research as a PhD student in physics at Stanford.

For cosmologists seeking to determine the fundamental properties of our universe, one item of special interest is the large-scale distribution of dark matter – in particular, its overall density and the degree to which it clusters into concentrated regions known as halos. Dark matter makes up about eighty percent of the total matter in the universe, and so measuring this distribution is essential for inferring how the universe was structured in the past, as well as how it will evolve in the future. Unlike the regular matter that comprises stars and galaxies, however, dark matter doesn’t emit or reflect light. As a result, it can’t be observed directly by telescopes, and so determining its distribution requires more clever approaches.

One such approach is to observe the positions of billions of galaxies using state-of-the-art survey telescopes and then, using the fact that galaxies form within the densest regions of dark matter (the halos), to infer the underlying dark matter distribution from the galaxy data. The relationship between the two isn’t simple and linear, however: a region with twice the average amount of dark matter (for a region its size) doesn’t necessarily contain twice the average number of galaxies. Working out the dark matter distribution therefore relies on having an accurate statistical model of the complex connection between the two distributions.

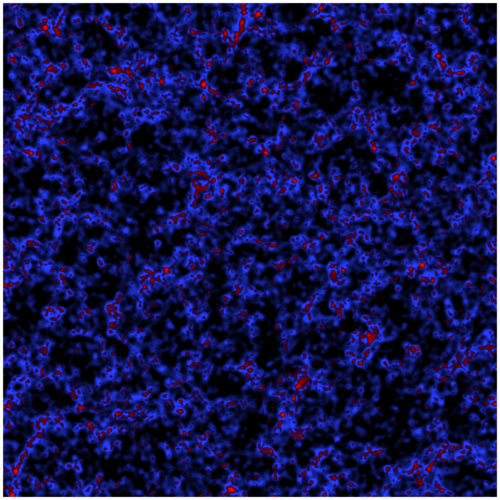

My research in Munich focused on improving our understanding of a specific aspect of the galaxy-dark matter connection. I developed a computational pipeline which utilizes the results of computer simulations of dark matter particles and their clustering into halos over time. By populating these simulated halos with galaxies in a realistic way (see figure), the pipeline allows me to compute galaxy counts in different regions, then analyze the amount of variation in these counts. Our understanding of this variance, and its dependence on the changing density of dark matter from place to place, turns out to be an important factor when calculating the dark matter distribution from galaxy data. By putting tighter constraints on the degree to which these galaxy counts can vary, my work is aimed at helping other cosmologists place correspondingly tighter constraints on their measurements of the properties of our universe.

In addition to the progress I made in this project, my time in Munich sparked a new collaboration which has extended beyond the internship itself. Together with Oliver Friedrich, a Fraunhofer-Schwarzschild Fellow, and Marco Gibietz, a master’s student in Professor Grün’s group, I am using neural networks to determine the minimum possible complexity of models which accurately describe the coupled distributions of galaxies and dark matter. This is an exciting new cosmological application of artificial intelligence methods which, rather than simply describing or generating data, can be interpreted in order to derive new mathematical models and physical insights.

I had a very positive experience living in and exploring Munich, and I’m eager to return if the opportunity for future collaborations should arise. The city is easily walkable and pleasantly uncrowded, with reliable public transportation which gives easy access to abundant parks and historic squares. As a language enthusiast, I also enjoyed the challenge of learning and practicing German, and I’ve continued studying since returning to Stanford with the goal of having more casual conversations with my collaborators in Munich. On the whole, this internship provided opportunities which wouldn’t have existed otherwise and made for one of the most enjoyable quarters of my PhD so far.

Research figure: A slice of the MultiDark cosmological simulation (Prada et al., MNRAS 2012) showing the large-scale distribution of dark matter (blue), which my computational pipeline has populated with galaxies (red) in the densest regions. The image shows a simulated volume which is roughly 3 billion light-years on each side.