Gaurav Kamat: Investigating Confinement Effects of Nanoparticle-Based Hydrogen Fuel Cell Catalysts

Gaurav Kamat: Investigating Confinement Effects of Nanoparticle-Based Hydrogen Fuel Cell Catalysts

Hydrogen fuel cells utilize sustainably generated hydrogen gas and recombine it with oxygen from the air to produce electricity on demand. The oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) is a widely studied half-reaction employed in fuel cells and other sustainable energy technologies for electrochemical energy conversion. Fuel cells exist as both proton exchange membrane (PEMFC) and alkaline (AEMFC) and carry out this crucial reaction at the cathode with the most common commercial catalysts being platinum (Pt)-based. Despite decades of progress in fundamental understanding and new catalyst formulations, ORR kinetics remain one of the largest sources of inefficiency in fuel cells so there is a need for higher performance catalysts that remain stable over device lifetime. With more viable non-precious catalyst formulations being developed in recent years, largely accomplished with nanostructuring catalyst materials, stability and local environment effects have remained relatively underexplored for non-Pt materials both theoretically and experimentally. During my internship at TU Darmstadt, my goal was to study the effect of geometric confinement for nanoparticle catalysts in several liquid environments that may mimic realistic device conditions.

Fuel cell catalysts for commercial applications typically consist of transition metal nanoparticles supported on high surface area carbon. These carbon supports can have varying levels of complexity in their surface and pore structure that enables them to sustain a higher active catalyst area, boosting performance. For my study, I evaluated Vulcan, Ketjen Black, and Hollow Graphitic Spheres which have increasing amounts of porosity in that order. Electron micrograph images shown in Figure 2 demonstrate the geometry of these carbon supports.

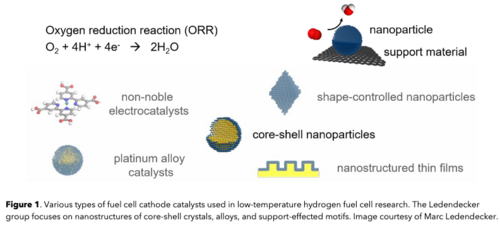

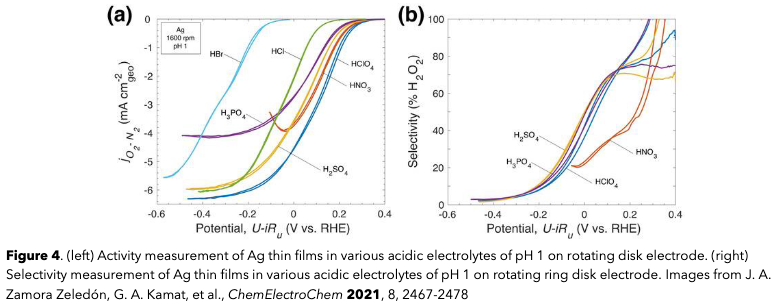

Another fundamentally interesting area of work is in the study of electrolytes and liquid environments within fuel cells, which have a significant impact on their performance. Here, performance means the activity (reaction rate) that the catalyst enables, selectivity (how favored the desired reaction is), and the stability (lifetime) of the catalyst. I used silver (Ag) as a model material as I have previously examined its electrolyte dependence for oxygen reduction, but that study was accomplished on Ag thin films such as the schematic shown in Figure 1. In Germany, I wanted to learn advanced synthetic techniques for embedding Ag clusters onto and within high surface area carbon particles to see the effect of confinement on performance. One way to accomplish this is with incipient wetness impregnation, a technique that uses capillary action to draw Ag atoms into the complex pore structure of the carbon support and encourage it to form a high surface area active layer.

The findings of this study would contribute to a growing field of non-precious alternatives to Pt for fuel cells, a crucial need for our carbon-neutral future. Germany, in particular, has a need for transitioning to sustainable energy sources to power a massive industrial and transportation sector. I was proud to see that the state of Lower Saxony (Niedersachsen) began operating the first hydrogen train line in Germany while I was there over the summer to much fanfare in the fuel cell community. In addition to industrial adoption, I got to go on tours of several industrial facilities during my time such as BASF in Ludwigshafen and Siemens Energy in Erlangen. There is immense interest from industry and government to develop these technologies, and I got to hear about this at a roundtable discussion with government officials from Hessen and the local transportation authority of the Rhine-Main-Neckar region. Finally, I attended a conference and had the chance to give talks at universities throughout Germany to other groups working in the space. The cultural exchange was invaluable in terms of seeing how groups solve problems together, manage their experiments, collaborate across borders, and create a welcoming workplace environment for visitors. I am continuing to collaborate with Marc’s group now that I am back at Stanford and I have no doubt that I’ll have something to look forward to in Germany in the future.

On a more personal note, living and working outside California for the first time in my adult life was an unforgettable experience. I met so many motivated people determined to solve the climate crisis. I learned about German national and state-level history, language, and cuisine at museums and festivals. I could travel throughout Germany on bike tours, the 9-Euro-Ticket, and buses to visit everywhere from Munich to Aachen.