Noah Youkilis: Transonic buffet in 2D linear cascades

Noah Youkilis: Transonic buffet in 2D linear cascades

Due to the funding and support provided to me through the Graduate Research & Internship Program, I was able to pursue a 12-week internship/research visit at the DLR (German Aerospace Center) Institute of Aeroelasticity in Göttingen, Germany. I worked with Jens Nitzsche and Dr. Holger Hennings in the Department of Aeroelastic Simulation on an ongoing project investigating the nature of transonic buffet in 2D linear cascades.

The DLR (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt, German Aerospace Center) is a German national research center, with various institutes located across the Federal Republic of Germany. Its broad focuses include aerospace, energy and transportation research, as well as managing the German space program. I was lucky enough to get connected with the Institut für Aeroelastik, or Institute for Aeroelasticity, in Göttingen, Niedersachsen. This department concerns itself with aeroelastic simulation, or using Computational Fluid/Structure Dynamics (CFD/CSD) to investigate research questions broadly involving fluid flow or fluid-structure interaction problems. As my research background is in CFD, the Institute of Aeroelasticity was a great fit.

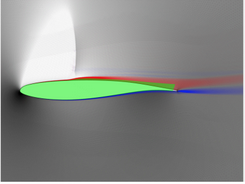

At the DLR, I participated in a research project looking at transonic buffet in 2D linear cascades. Transonic buffet is an experimentally and numerically observed fluid-mode instability, occurring at specific transonic flight conditions, for certain airfoils (or wing cross-sections). It is characterized by large-scale shock oscillation and shock-boundary-layer interactions, with accompanying large-scale oscillations in the lift, and occurs even when the airfoil does not move. The physics behind this phenomenon are not well understood. In other words, for a given airfoil, we do not have a means of predictingwhether transonic buffet will occur, and if so, at which operating points it will occur. Predicting this domain of instability therefore requires brute-force numerical computation across different flight conditions. Figure 1 shows a URANS simulation of the OAT15A airfoil exhibiting transonic buffet, with the grayscale coloring showing the pressure field (and therefore the shock), red-blue the vorticity field, and green the boundary-layer displacement thickness. As the shock recedes (moves left), the boundary layer grows, and as it progresses (moves right), the boundary layer shrinks.

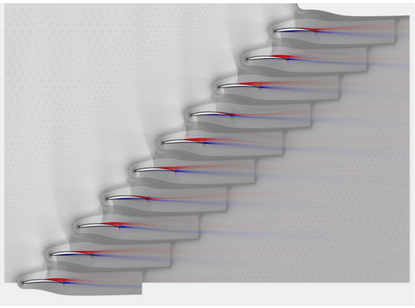

Shock buffet has been thoroughly investigated, experimentally and numerically, for these sorts of fixed-wing (single) airfoils. The project I participated in, however, aims to investigate this phenomenon in the case of turbomachinery flows--if, where and how it occurs, as well as how it differs from traditional fixed-wing buffet. The primary configuration being investigated is Standard Configuration 10 (SC10), a 2D linear cascade. To this end, after familiarizing myself with the DLR Tau CFD code and fixed-wing shock buffet, I started working with SC10. Figure 2 shows a sample URANS simulation of shock buffet occurring on SC10, with ten passages simulated and periodic boundary conditions at the top and bottom. Again, grayscale coloring shows the pressure field and red-blue shows the vorticity field.

At this stage of my internship, I performed a variety of different studies so that the research group could get a feel for what shock buffet in these kinds of linear cascades looks like. I simulated many different combinations of angle of attack and exit pressure, to get a sense of the shape of the instability envelope. In addition, I investigated the effect of parameters such as pitch/chord ratio (or the distance between successive blades), inlet and outlet distances, and number of passages. In the second half of my internship, I pivoted to helping develop a framework to be able to structurally perturb individual blades separately from one another. Such a framework would enable further studies needed to move the project forward, such as looking at eigenvalue stability analysis of the fluid field. This work is not yet complete, which led us to identifying the need for further collaboration after my return to Stanford. In addition to contributing to the project, I learned a lot from my colleagues at the DLR. Whereas my background lies in CFD method development, the work I performed this summer instead focused on using CFD as a tool to better understand physical phenomena, which was interesting and eye-opening for me.

Outside of work, I also had an amazing experience living in Göttingen for three months. I was fortunate enough to be able to live in a Wohngemeinschaft, or shared flat, with five Germans around my age. Be it cooking together, going on walks, or going to the farmers’ market, I had a built-in community, which made my experience truly memorable. Being surrounded by Germans had the added benefit of helping me to revive my rusty German, which was a huge perk. I was also able to travel on the weekends and visit parts of Germany I would not have otherwise, thanks to the Nine Euro Ticket. My biggest highlight, however, was the time I spent on my bike, which I brought with me from California. Biking helped me meet people and get to know the landscape around Göttingen. Particularly special were the Tuesday evening DLR bike club training rides, where I got to know a subset of my colleagues outside of work. I regularly biked to Hessen and Thüringen, and even to Sachsen-Anhalt once on my way to summit Brocken, the tallest mountain in northern Germany. I look forward to wearing my new black-and-white DLR jersey on bike rides around Stanford.

All in all, this summer provided me with a holistic glance at what life would be like living and working in Germany. I am beyond grateful for this opportunity, and I cannot wait to be back.